Speak to our experts

Contents

The New Zealand - United Kingdom Free Trade Agreement (FTA) signed on 1 March by Trade Minister Damien O’Connor and his United Kingdom (UK) counterpart, Anne-Marie Trevelyan, is by almost any estimation, a big deal.

It has a lot to offer goods exporters immediately, and New Zealand consumers down the line, if innovative British service providers decide to test their ideas here, and will clear the way for young Kiwis to do their “OE” in the UK. The FTA is anticipated to take effect later this year or early 2023.

We take you through the highlights of the deal and the process from here.

Taking a blowtorch to tariffs

All customs duties on bilateral trade are to be removed. Almost 70% of current New Zealand exports to the UK (including wine, honey, kiwifruit and onions) will become eligible for duty-free access to the UK as soon as the FTA enters into force, with remaining duties to be phased out over specific timeframes, including:

- butter and cheese after five years (with interim reductions during that period), and

- beef and sheep meat after 15 years.

Quotas will also allow a increasing volumes of these products to enter duty free during the five and 15 year phase-in periods.

There is considerable scope for export growth as, for all products, the agreed quota volumes exceed our current export levels, and all customs duties will be eliminated after the quotas cease to apply.

There is also good news for Kiwi wine exporters. The FTA provides that the UK will recognise immediately a number of New Zealand winemaking practices (listed in a specific Wine and Distilled Spirits Annex) and will assess further practices, with a view to affording those recognition in due course.

The UK has also agreed not to require the administratively burdensome VI-1 certification for wine (originally an EU requirement that imported wines be accompanied by an import certificate), or any subsequent certification with equivalent requirements.

Services sector

The deal sets out commitments to facilitate and provide certainty of access and regulatory conditions for services exporters and investors – including financial services, tourism and education.

A key interest for the UK – as with any of its FTA negotiations – is financial services, which is the largest exporting service sector in nearly every British region. This focus could produce potential benefits for New Zealand consumers – e.g., if innovative British fintech companies look to test new services and products here.

Which they may well do as, while New Zealand and Australia (which also recently signed a trade deal with the UK) may be relatively small markets individually, together they can provide a gateway to the broader Asia Pacific.

The importance of the digital economy is recognised in the Digital Trade Chapter, which seeks to promote user confidence by advancing the inter-operability of regulatory frameworks and systems, avoiding unnecessary barriers, and supporting “digital inclusion”. It also contains various safeguards to ensure that New Zealand and the UK can regulate to protect matters of public and social interest, such as privacy and national security.

This Chapter is likely to come under particular public scrutiny given the recent Waitangi Tribunal finding that the Crown, in negotiating the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), failed to protect Māori rights and interests in data and the digital domain. The Chapter creates space to address any concerns that may arise, with a clause providing for a review to take place within two years of the Agreement’s entry into force.

Also of note for prospective “OE-ers” is the commitment to extend and improve the existing New Zealand-UK Working Holiday/Youth Mobility Scheme, which allows 18 – 30 year olds to apply for two year working holiday visas. Details of extensions are still to be negotiated.

Inclusive trade and broader societal concerns

The FTA is cutting-edge contemporary in terms of its engagement with broader issues around inclusive trade, climate change and other matters of societal interest such as animal welfare.

Highlights include:

- a Chapter on Māori Trade and Economic Cooperation which reflects the special relationship between Māori and the British Crown as original signatories to Te Tiriti o Waitangi/the Treaty of Waitangi, and the unique context arising from this and aims to promote cooperation between New Zealand and the UK to “to enable and advance Māori economic aspirations and wellbeing”

- a Side Letter in which New Zealand and the UK each acknowledge Ngāti Toa Rangatira’s guardianship of the Haka Ka Mate

- a Chapter on Animal Welfare – a first for New Zealand. This provides for the establishment of a Joint Working Group on Animal Welfare to improve and advance the protection afforded to the welfare of farmed animals in animal welfare laws and regulations, and

- a Trade and Labour Chapter, which contains provisions promoting non-discrimination and gender equality and commitments on identifying and addressing modern slavery in each Party’s domestic and global supply chains.

There is also a substantial Environment Chapter, which includes provisions to address government subsidies (particularly on fisheries and fossil fuels) and commits the Parties to work together to address climate change.

The Environment Chapter also recognises each Party’s right to establish its own priorities and levels of protection relating to the environment, including mitigation of, and adaptation to climate change. And it provides the first acknowledgment in any international treaty of the special relationship of Māori with the environment in New Zealand, including reference to the concepts of kaitiakitanga and mauri of the environment

It also includes the largest Environmental Goods List ever agreed for an FTA, which designates over 290 environmentally beneficial products as priority goods for enhanced trade and tariff elimination.

There are also chapters on Gender Equality, Trade and Development, Consumer Protection and Anti-Corruption.

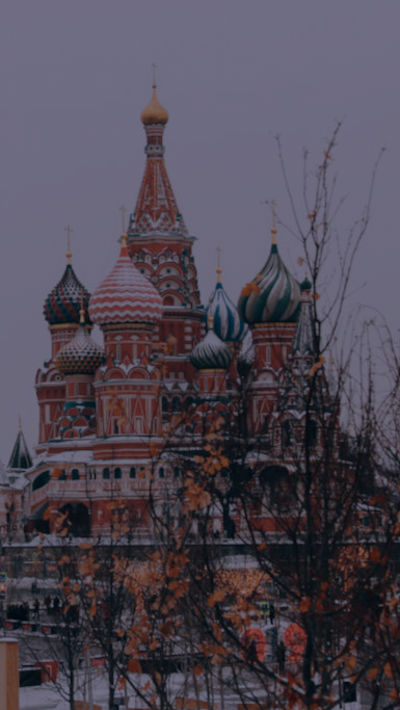

Strategically important

In a foreword to a 2021 review of the UK’s security, defence, development and foreign policy settings, Prime Minister Boris Johnson stated:

“By 2030, we will be deeply engaged in the Indo-Pacific as the European partner with the broadest, most integrated presence in support of mutually-beneficial trade, shared security and values”.

For the UK, the FTA is part of this broader “tilt to the Indo-Pacific”1 which aims to pursue trade opportunities shaped by national security concerns, while offsetting the economic costs of Brexit.2 Relatedly, the UK is also engaged in accession negotiations to join the CPTPP.

Next steps

Both New Zealand and the UK must ratify the Agreement before it can come into force. For New Zealand, this involves examination of the treaty text and a National Interest Analysis by the Foreign Affairs and Defence Select Committee. Parliament will then consider legislation required to give effect to the Agreement. The earliest the Agreement is likely to come into force is late 2022.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (MFAT) guide to the FTA is here.

1 “Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy”, online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/global-britain-in-a-competitive-age-the-integrated-review-of-security-defence-development-and-foreign-policy/global-britain-in-a-competitive-age-the-integrated-review-of-security-defence-development-and-foreign-policy

2 https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2022/02/01/prospects-for-the-united-kingdoms-cptpp-accession/