Speak to our experts

Contents

There is a lot of criticism and uncertainty around the application of directors' duties in New Zealand at the moment. There are some similarities with Australia’s situation after the GFC, where some commentators felt that Australia had some of the toughest directors' duties laws in the world.

One of the solutions employed in Australia was the introduction of an insolvency safe harbour, which shielded directors from personal liability for continuing to trade a distressed company if professional restructuring advice was obtained and the company continued to pay taxes and other costs.

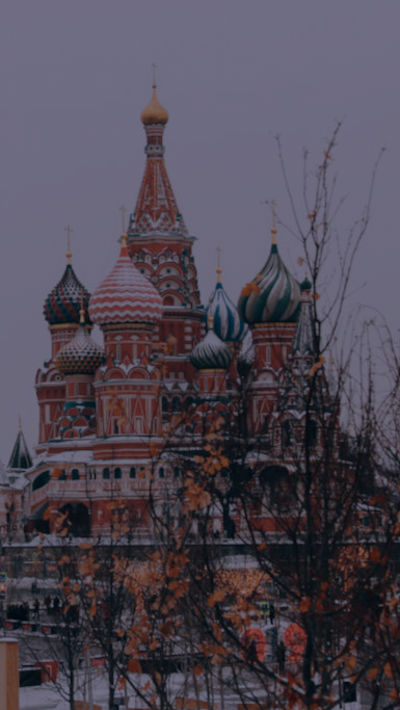

Finance Special Counsel Joshua Jones speaks to David Walter at Allen & Overy Sydney on the practicalities of the safe harbour and what the future of insolvency law in New Zealand might look like.

David Walter, Partner at Allen & Overy

David is a Partner in Allen & Overy’s Asia Pacific Restructuring and Recovery Group. He has extensive experience advising the spectrum of stakeholders in informal restructures and formal insolvencies, including public companies and their boards, private equity and portfolio companies, special-situations investors, bank lenders, trustees and insolvency practitioners. He focuses on non-contentious and contentious restructuring and insolvency assignments.

Q: What was the solution in Australia – briefly, how does the safe harbour work?

As you mention, the insolvent trading “safe harbour” has been introduced into Australia – in operation since 2018.

The “safe harbour” is intended to soften the pretty harsh edge of our “insolvent trading” duty. That insolvent trading duty is infamously tough – raising both civil liability and criminal risks for directors of companies in financial distress. And in an environment where availability of insurance coverage for those liabilities is very limited (or zero).

In broad terms, the “safe harbour” is a procedure that effectively dis-applies the insolvent trading duty while the safe harbour is being properly implemented.

The core requirement of safe harbour is that the board develops and then implements a “better outcome plan”. The plan is to keep trading the company through a turnaround process – with that turnaround process reasonably expected to produce a better outcome for the company when compared to immediately placing it in the hands of an administrator or liquidator.

It is important to emphasise that the plan does not necessarily need to completely avoid a formal insolvency. An effective plan can, for instance, simply be to properly prepare for a subsequent administration – with experience telling that a properly planned administration is almost always better than an unplanned “free-fall”.

The safe harbour then also imposes some sensible “hygiene” requirements on the board – keeping employees paid current, tax filings up to date, company records in good shape, and using an appropriately expert advisor to help guide the process.

It is important to emphasise that the safe harbour does not excuse directors from their core general duties – care and diligence, acting good faith in the interests of the company (including having regard to its creditors), and avoidance of conflicts. Those general duties remain in place – and in my experience are now rightly back in focus as the key focus for directors of companies in distress.

Q: What are the major advantages and disadvantages of the safe harbour?

Dealing with the bad news first: the disadvantage is that the “safe harbour” has not been tested in any court proceedings (perhaps a good thing for directors!). So the boundaries and expectations of safe harbour are in this sense unknown.

That issue is, I think, mitigated by the breadth and relative simplicity of the procedure – there is not great concern in the market about the lack of judicial decisions at this point. But some caution in using safe harbour is sensible, recognising this uncertainty.

The obvious key advantage is the liability protection for directors – any director facing a company in distress would, in my view, be mad not to consider safe harbour.

Beyond this, the key advantage is that the procedure sets up an environment for considered and well planned turnaround. Experience tells that time is almost always a friend in a turnaround or restructuring. As I said earlier, that time might be used to restructure or turnaround outside of formal insolvency – or it might be used to effectively plan an administration.

Q: How frequently is the safe harbour used today?

In my experience, the safe harbour is being used (where appropriate) in the middle-market and at the “top end of town”. So the market adoption has been very good. And the restructuring profession has skilled up and done a good job raising director awareness.

An interesting observation is my personal view that – picking up on my earlier general duties comment – directors run the risk of not acting in the best interests of their company if they do not consider relying on safe harbour to continue trading and explore a turnaround or restructuring. This picks up my point around safe harbour being a valuable formal insolvency planning tool – experience tells that taking some time (in safe harbour) to properly plan a formal insolvency is often a better outcome than an immediate, unplanned “free fall”.

This said – a recent government review has uncovered a need to do some more on small business using the procedure. Given that a lot of Australian insolvencies are in that part of the market, this is an important area for effort and improvement.

Q: How is the safe harbour working practically?

Very well in my view – and this is reflected in positive feedback from the recent government review.

A number of noticeable improvements have arisen:

- There is less concern amongst directors about insolvent trading liability risk, and the lack of effective insurance coverage. This keeps directors focused on the turnaround or restructuring – and less on personal risk management. A good thing.

- There are far fewer instances of directors precipitously or prematurely putting companies into administration or liquidation. As I’ve said earlier, that typically sees value destroyed for creditors – in contrast, we are seeing better planned administrations, leading to better creditor outcomes.

- Earlier use of restructuring professionals is seeing more realistic, experienced and granular focus on turnaround and restructuring (and less ignorance or postponement of difficult discussions and analysis). Getting those professionals involved earlier gives more time – and time gives more options.

In contrast, I have not seen anything negative arise from the safe harbour procedure.

Some commentators were concerned about safe harbour being used to promote “phoenix activity” – but I see no evidence of that being true. “Phoenix activity” is part of the insolvency landscape – but safe harbour does not enable or contribute to that kind of misconduct, I don’t think.

So, in practice a bunch of good outcomes – and no evidence of clear negative impacts.

Q: Have you got any tips for New Zealand?

The evidence from the recent government review is, ultimately, quite clear – this kind of procedure, enabling earlier consideration of restructuring and turnaround, is a positive for stakeholders in distressed companies.

New Zealand practitioners should be pushing government to consider similar measures for New Zealand – if needed. Safe harbour might not be the perfectly right answer for New Zealand – but hopefully gives New Zealand practitioners a steer in the right direction.

Beyond law reform – I often say that good practitioners always look at innovative or creative ways to use the tools that are available. So, don’t allow slow law reform or the absence of a “safe harbour” style procedure to get in the way – think about how the existing administration procedure can be better deployed, and the existing director duties landscape can be better navigated, to get better outcomes for stakeholders.

This article is part of our regular publication Restructuring & Insolvency: Rescue & Recovery. Read the other articles in this series below.